The Mennonite Family Stalter in Gern

By Herbert HollyNeuhauser Werkstatt-Nachrichten, 46 (June 2021): 50-53.

The following article was published in German in “Neuhauser Workshop News,” and is added to this website with the permission of the author. Thanks to Sem Sutter for translation assistance. Photos of three farms are shown below the article. Persons mentioned in the article that are included in this website are linked to their information in the Family Tree.

Heinrich Stalter the Elder, born 1725, was leaseholder of the Kirschbacherhof in the Palatinate for a period of time.

Photo: Donna Birkey, 1984

The local historian Herbert Holly from Hofolding has been pursuing the history of the Gern Mennonites for a long time. So it is no coincidence that he came into contact with the history workshop and agreed to write this article for the workshop newsletter, for which we thank him very much.

In issue No. 26 of the Neuhauser Werkstatt-Nachrichten we dealt with the Nymphenburg district of Gern as the main topic, and also reported that the Anabaptists (Mennonites) settled in Gern around 200 years ago. The Mennonites residing in Gern belonged to a split from this religious denomination, the “Amish Mennonites,” named after their founder Jakob Ammann.

Hardly any other Amish Mennonite family in the Duchy of Zweibrücken had such good contact with the Wittelsbachers as the Stalter family. Since they had leased one of the ducal estates, the children of the Stalter family grew up with Prince Max Joseph, who later became Elector and King of Bavaria.

The Amish Mennonites, who originally immigrated from Switzerland via Alsace to the Palatinate, were almost exclusively farmers. Because of their beliefs, they had to leave their homeland in Switzerland because it was not possible to get along with the authorities. They would not take an oath, refused to do military service, and would not hold public office. They were warned and locked in prisons and if that did not help them to give up their beliefs, they had to leave their homes and farms. Their principle of belief was strictly based on the biblical Sermon on the Mount. Since they did not seek ownership of property, they generally appeared as tenants. The nobility used this peculiarity to offer the Mennonites the opportunity to farm the large estates in the best possible way.

When secularization began in Bavaria in 1803, the former monastery estates that were no longer being farmed were released for purchase and lease. With a special appeal in the Palatinate and Alsace, the first Amish Mennonite families came to Bavaria in 1803, among them also the Stalter family. They farmed some estates in the Neuburg and Ingolstadt area. Already in 1803 Max IV Joseph, who by then reigned as Bavarian elector, offered Heinrich Stalter the “Diessener Hof” in Gern, but this did not materialize because Stalter was able to lease larger properties, namely the Bergstätterhof and Neuhof near Kaisheim. Stalter’s self-assurance also took remarkable forms. He criticized the “State Commission for Monastery Affairs” for having sold the Thierhaupten Abbey estate near Aichach too cheaply in his opinion. For this, he received a reprimand from Munich.

But the good connection to the elector, and later king, Max I Joseph came about through his relationship with Heinrich Stalter the Elder (ID61), leaseholder of the Kirschbacherhof in the Palatinate. This was very important to the king because when the French stormed Karlsberg Castle near Zweibrücken, Heinrich had helped Duke Karl August, who was Max Joseph’s older brother, to escape with his life by giving him shelter for one night and then taking him across the Rhine. Two years later, in 1796, Duke Karl August died in Heidelberg. The elector and later king had not forgotten the rescue by the Stalter family.

A document reports that a Stalter in Gern was already active as a tenant around 1808. This emerges from Christian Jotter’s 1836 application to emigrate, in which he stated that he married Katharina Augsburger, née Stalter, in Gern in 1808 and that both were employed by Jakob Stalter, an agricultural estate tenant in Gern, and then moved to Weilbach near Dachau as tenants of Count Spreti. This Jakob Stalter, who later moved back to the Palatinate where he died in 1819, was the uncle of the Stalter brothers who bought the farms in Gern in 1830. Unfortunately, we don’t know which farm he ran in Gern.

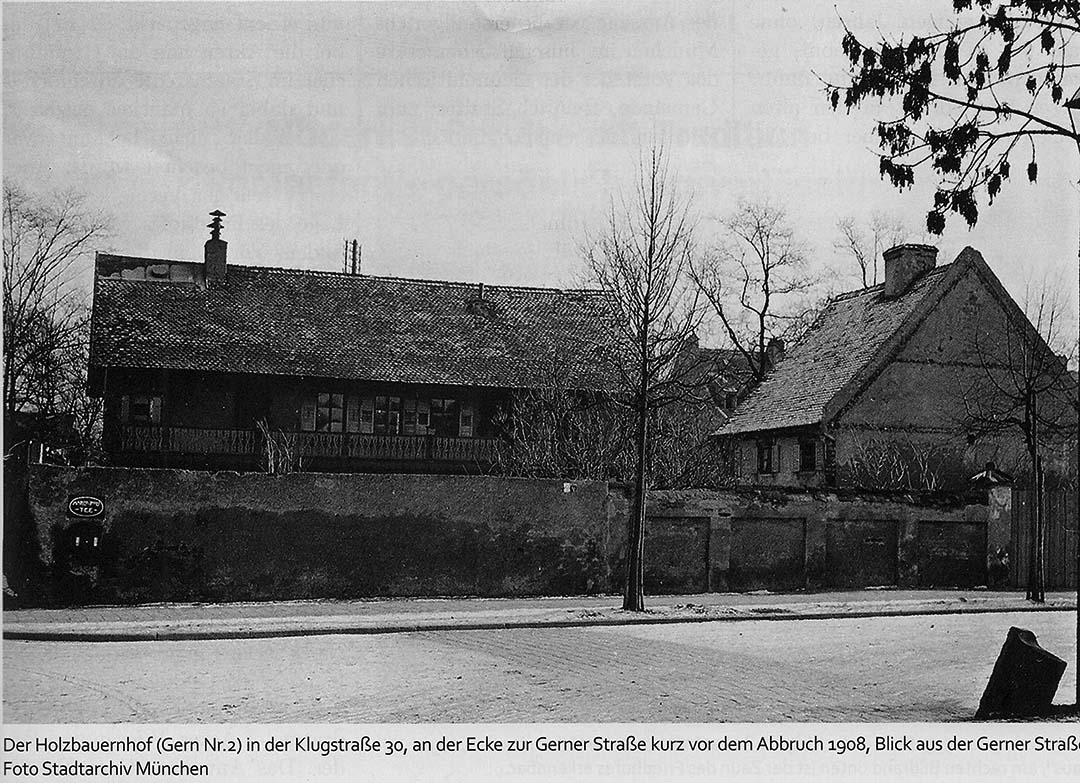

The queen widow Karoline had already tried in 1826 to sell three agricultural properties she owned in Gern and had therefore advertised them in newspapers. The sale was delayed, however, because it was only four years later, on August 6, 1830, that Heinrich Stalter (abt. 1780-1851) acquired the three advertised farms in Gern from the royal civil list together with his brothers Joseph (ID85) and Jacob (ID778). These were the property “Gern No. 4,” the “Oswaldhof” (the later “Gern Brewery at Klugstrasse 21) with 283 Tagwerk [an old measure] of land (= around 940,000 square meters); the house number “Gern 3,” the Kandlerhof (was at today’s address Klugstrasse 29) with 219 Tagwerk (= around 750,000 square meters); and the house number “Gern 2,” the “Holzbauernhof” (at today’s Klugstrasse 30) with 155 Tagwerk (= around 530,000 square meters). Eduard, Count of Yrsch, undertook the securitization for the queen widow. The farms were sold including machinery, livestock, and currently standing crops. The Oswaldhof cost 4,050 guilders, the Kandlerhof 4,220 guilders, and the Holzbauernhof 2,720 guilders.

In 1835 Heinrich Stalter had to submit a statement to the district court in Munich and report on the religious community of the Amish Mennonites in Munich. In doing so, Stalter pointed out that he could only testify about the “Häftler” and not the “Knöpfler.” (There were differences among the Mennonites: the moderate ones were the “Knöpfler,” the strict ones were the Amish, the “Häftler.” This was recognizable on their clothing—while buttons were present on that of the “Knöpfler,” the “Häftler” wore only joiners, so-called hooks and eyes. Stalter then reported the following: the first Amish religious community in Munich was founded at the beginning of the 19th century. Heinrich Stalter was their leader. He also gave information about the number of Amish families in Munich as well as the form of worship services: baptism, the Lord’s Supper, marriage, and burial.

In the 1840s the urge to emigrate on a larger scale also included Amish Mennonite families. Families who had already emigrated to Canada and the USA wrote to their old homeland about the advantages they found and the freedom that prevailed there. In a letter that the Amish Mennonite Daniel Unzicker (ID8885) wrote to his mother in 1826, he says, “We are doing very well here in Upper Canada. The harvest is double that at home and the price is also right. I have many maple sugar trees that bring abundant harvests. Also, it decays very quickly when one prepares a field for grain, so one can plant the seed into the earth in a short time. Dear mother, leave everything behind and come soon with the dear siblings; there is enough space with me and we have a good life.”

Heinrich Stalter also considered the idea of emigrating. His wife was against it, although there were already three children in the United States. It was only after the death of his wife that Heinrich made the decision to emigrate with his family. His two daughters, Katharina (ID7564) with Christian Jordy (ID6304) and Elisabeth with Georg Keltner, both from Gern, had emigrated to America in 1839. [After contacting the author on 28 Aug 2021 about the previous sentence, he agreed it is in error and should read: “His two daughters Katharina, with Christian Jordy, had emigrated to America in 1839 and Elisabeth (ID96), second wife of Christian Birki (ID97), in 1851.”] In 1840 they sent their father a power of attorney from New Orleans to sell the farm with their consent and take their share of the proceeds with him if he emigrated to America. The father would find food and accommodation with them for life. The invitation encouraged Heinrich Stalter to emigrate. He applied to emigrate on August 28, 1841, which was also approved. He sold his Holzbauern property in Gern to Willibald Brodmann in Munich for 10,766 guilders. After deducting the obligations and mortgages, Heinrich Stalter had 7,766 guilders. From this, their share of the property went to his children in the amount of 3,883 guilders. The other half remained in his possession. The guardian of the three children who were still minors, Christian Roggy, an Amish Mennonite in Unterhaching, had given his consent to the sale, emigration, and property distribution. When he left, Stalter gave the shepherd’s house that belonged to his property to its residents. For this gift to take effect the previous owners had to send a notarized power of attorney from America. The shepherd’s house in Gern was north of the Canaletto, just after the bridge at what is now the Nederlinger Platz. The full correspondence with all original documents is in the Munich State Archives.

Joseph Stalter sold his Oswald property to the Baron von Welden for 14,500 guilders. He also planned to emigrate, because when he sold it, he stated that with the 6,000 guilders he had left he had the prerequisite to be able to emigrate. But then he decided differently and bought the “Zieglergut” in Neufahrn near Wolfratshausen.

Jakob Stalter transmitted his Kandler property to his son-in-law Valentin Bircki (ID36) and his wife Elisabeth (ID37) on March 8, 1833. The two had paid their parents 8,140 guilders in cash. Valentin Bircki stayed on the farm until 1849, when he applied to emigrate to family members in Illinois, USA. He sold 67 Tagwerk to Baron von Welden for 10,400 guilders in 1846. He sold the rest of the farm to Friedrich Fries for 16,000 guilders in 1849. Then he left Germany with other Amish Mennonites. Thus ends the story of the Amish Mennonites in Gern.

Sources

- Staatsarchiv München: files from the Springer collection

- Hauptstaatsarchiv: MI 18192, MF 16792, 63152

- Hermann Guth, “Mennoniten im Gunst eines Fürsten,” (Mennonites in a Prince’s Favor)

- Hermann Guth, “Mennonitenfamilien Stalter,” (The Mennonite Family Stalter) both articles appeared in the Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, Weierhof, Palatinate.

- Dr. Hermann Hage, “Amische Mennoniten in Bayern ab 1803,” (Amish Mennonites in Bavaria from 1803 on), dissertation, University of Würzburg, 2009

Aerial photo of 1916: the white band on the left is the Klugstrasse on which the Kandlerhof (Gern No. 3) is visible on the lower left, opposite the junction with the Kratzerstrasse. Photo from the Munich War Archive.

At the left Gern No. 1 (Ballauf); to the rear behind the tree, Gern No. 4, the former Oswaldhof, later the Gern Brewery; photo ca. 1897

The Holzbauernhof (Gern No. 2) at Klugstrasse 30 on the corner of Gerner Strasse, shortly before its demolition in 1908; photo from the Munich City Archive.