Grandma Josephine Yordy Schrock

Person of Resilience and Servanthoodby Frank Kandel, with cousin Donna Schrock Birkey

Grandma’s ancestry

My Grandma, Josephine Yordy Schrock (1886-1977), was the third of nine children born to the union of Elizabeth Roeschley (1862-1953) and Joseph Yordy (1857-1925). Her maternal grandfather, John Roeschley (1812-1881), operated Hoser Mill on the Illinois River near what is now Spring Bay for about ten years. Farmers brought their grain to the mill to be ground into flour by two large stones powered by water flowing from Partridge Creek to the Illinois River. Her maternal grandmother was Elisabeth Saltzman (1826-1891). The paternal grandparents were Peter Yordy (1815-1897) and Maria Birky (1816-1903).

Most likely one of the millstones used at Hoser Mill in Spring Bay

Josephine’s father Joseph was a bit of a wanderlust, not infrequently moving his family from place to place seeking economic opportunity and adventure.

According to his obituary, after Joseph’s marriage to Elizabeth Roeschley, they lived one year near Roanoke, fifteen years near Flanagan, twelve years near Fisher and the final years in Woodford County, at Plainview farm and lastly at a home in Eureka where he died.

However, during his lifetime he left Illinois several times. In 1903-1904 the entire family was in California, in 1912 a trip to Texas. He also traveled alone to Washington, D.C. to satisfy his curiosity about the seat of government.

Joseph owned two farms, with hired men doing the actual farming, so he probably took out a loan for the 1903-1904 family trip, with the thought of eventually moving to California. Perhaps to retire—better weather than Illinois!

On a Tuesday Joseph and Elizabeth with eight children, plus a cousin (Lewis had not yet been born) boarded a train in Mahomet to Peoria, then to Chillicothe. Leaving Illinois they had a sleeping berth for three nights that became seats during the day. They took their own food along. The plan was to remain for two winters. On arrival, they stayed in a hotel until renting a house, at which time they bought furniture, and settled in. The older children worked outside the home. On the way back to Illinois they stayed in Colorado Springs for six weeks.

But in the end Joseph decided against any move and the family lived their entire lives in Illinois. Grandma Josephine was seventeen at the time this adventure.

The Joseph and Elizabeth Roeschley Yordy Family: Back row L to R: Josephine Schrock, Aaron, Ezra, Ella, Anna; Front row L to R: Jonas, Joseph, Baby Lewis, Alvin, Elizabeth, Walter

During his lifetime Joseph served as a deacon at Roanoke Mennonite Church. He was known as a “man of good judgment” by both the church community and town people. Singing found a great place in his life, and he always took an active part in worshiping God in song. We are told he would often yodel while resting in the evening in his chair by a fire.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised about all the moving families did in the early days of their lives in America, considering their European Mennonite heritage where families seemed to always be on the move. It is said of Joseph’s father, Peter Yordy, (born in Jaegerthal near Windstein, France, later an 1838 immigrant from Hanfeld, Bavaria, Germany) that he landed in Pekin, off the boat on the Mississippi River, “with lice in his hair and ten cents in his pocket.” Yet, about thirty years later, being very interested in education, he sponsored an English class for Amish children in his home.

The History of the Family of Peter Yordy – 1815-1897

At one point Peter purchased a specific property in order to donate one acre for a school. Subsequently, a legal question arose about property taxes, resulting in forty-three property owners being required to pay a prorated portion of the $7000 required amount. Recognizing that Peter had only purchased his property to donate for a school, the other owners paid Peter’s share of the tax. His legacy of the importance of education has been passed down through generations of his descendants, including my Mom, Eunice.

Joseph Yordy’s 1898 foray into Champaign County landed his third daughter Josephine into the arms of Albert Schrock, a sickly lad from Fisher, Illinois.

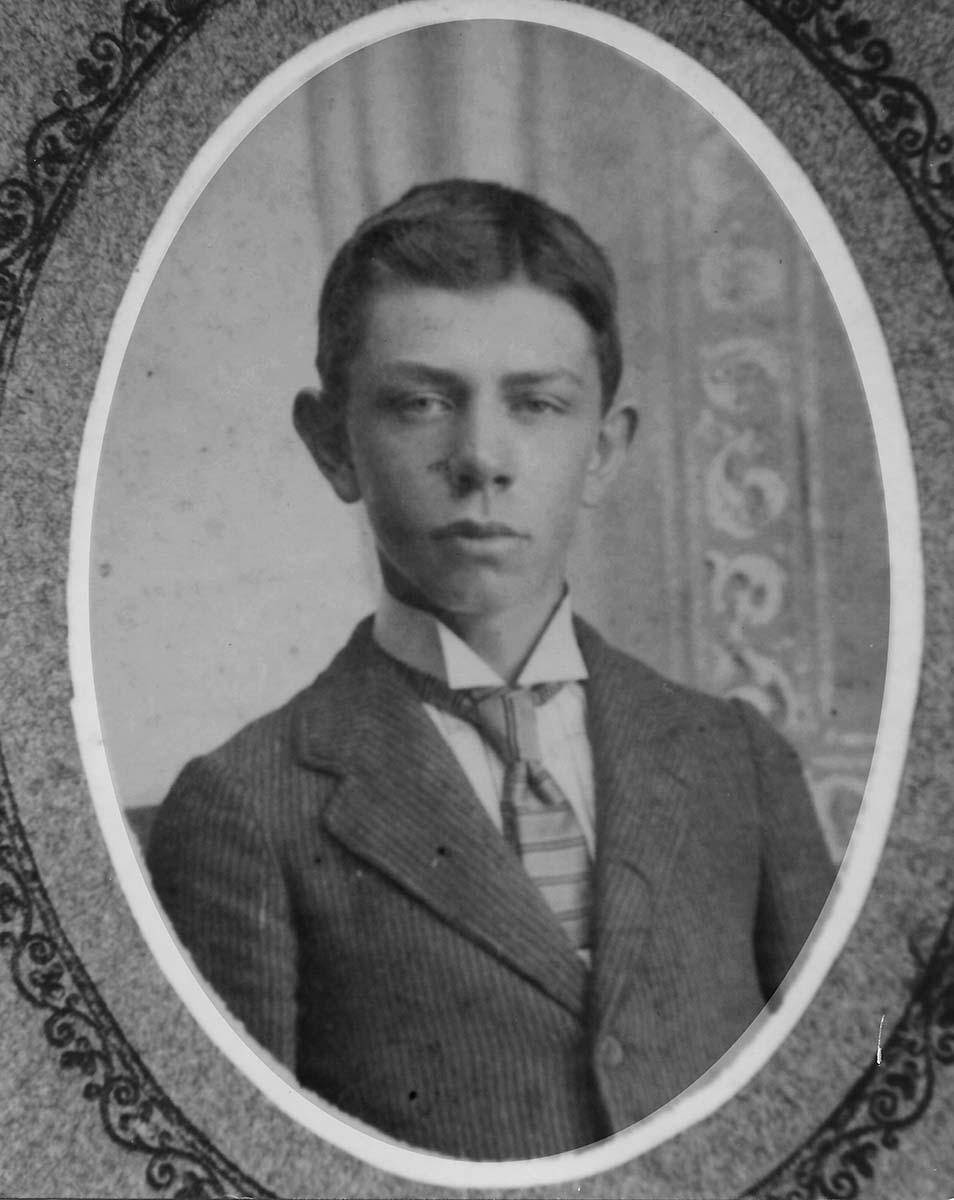

Albert Schrock in his early teens

Albert’s great-grandfather, Johannes Schrock, had come to Illinois via the Mississippi River, also landing at Pekin. The rural area five miles east of Pekin had become a welcoming station for Amish Mennonites migrating west, greatly due to the hospitality of the Andrew Ropp family. This area was the beginning of the Dillon Creek Amish settlement four miles southeast of Pekin on Old State Rd.

According to his obituary, “The [Johannes Schrock] family located in a log house on what is now the Allen Miller farm five miles east of Pekin [previously owned by Andrew Ropp]. They were made at home by the Mennonites here and kindly neighbors; and because they were honorable and thrifty, they prospered.”

Grandma’s early life

Josephine was born on a farm about a mile from Flanagan. Later the family moved to Fisher where they had a large orchard of fruit trees at the intersection of Routes 47 and 136, and a very large garden. They also cured hams, hung in a smoke house, and kept meat through the winter in crocks covered with heavy brown paper. Items would freeze and refreeze, but they ate it without resulting sickness. Being self-sufficient with no electricity, a coal stove, and an outhouse, they had no monthly bills to pay except for the telephone, when it finally arrived.

Grandma walked one mile to Allison School, which she attended through eight grades: her husband-to-be, Albert Schrock, went to Brown School. When modern conveniences finally began arriving, the telephone was a party line with many people on the line. Her first car ride was with Henry Ingold. Grandma later bought a radio when she and Eunice went to Goshen, and also bought a Ford touring car in 1919 for $900, plus $100 to upgrade from a crank to electric starter. There was no hesitancy on her part to make use of those newly available modern conveniences!

In Champaign County, Joseph Yordy’s family attended East Bend Mennonite Church. In Sunday school they learned German, only later were classes held in English. Father Joseph took part in church life, even speaking at times. But it was not easy for him.

Eventually, Josephine and Albert courted in a carriage and were married by Peter Zehr in the parent’s home. There were no “witnesses,” only the small number of people who were invited and attended, perhaps twenty or so. It was a morning wedding, with a large midday meal served to all. Grandma remembers roast goose being served. Guests brought part of the meal, potluck-style. In the evening the young people of the church arrived to finish up the food, play games, and enjoy themselves along with the bride and groom.

The newlyweds lived first in a house east of Fisher where Elmer was born (house no longer remains). They soon moved to a farm south of Fisher, where Orval was born—later owned by the Unzicker and Deffenbaugh families.

When the effects of a severe case of measles as a child left Albert with poor health and weak lungs, he later contracted tuberculosis and became sick. The couple had a farm sale and moved to Colorado with their two boys—the mountain air was thought to aid healing.

Unfortunately, my grandfather Albert Schrock was not able to experience the wanderlust of his ancestors. At the young age of thirty-one, after four years of fighting the disease, he was struck down in 1917 by a tuberculosis-induced coughing fit while pumping water at the family well. Josephine’s son, Orval, later said about his mom, “she was asked [after Albert’s death] by several to marry, but evidently she wasn’t enough impressed by those who asked to accept.”

The Untimely Death and Exemplary Life of Albert E. Schrock

My Grandma Josephine, pregnant with her third child, carried on best she could managing the forty-acre farm with the help of her boys Elmer and Orval, and her in-laws who lived next door—John and Mary (Birky) Schrock, and the Joseph A. (J.A.) Heiser family. J. A.’s wife, Fannie, was a sister to Albert, thus the sister-in-law of Grandma Josephine. My mother, Eunice Lois (1917-2002) was born on June 25, 1917, just six months after her father Albert died.

Following Albert’s death the family was given forty acres close by to farm. Grandma’s brother-in-law, J.A. Heiser, and her boys farmed twenty acres; she paid J.A. to farm the other twenty acres. Grandma got the boys off to school, then she would husk corn, and care for the cows and pigs. Then came the Depression, but they made it through by Grandma Josephine working in various homes as housekeeper/ caretaker after the boys were married.

Josephine with her children: Orval, Elmer, Eunice

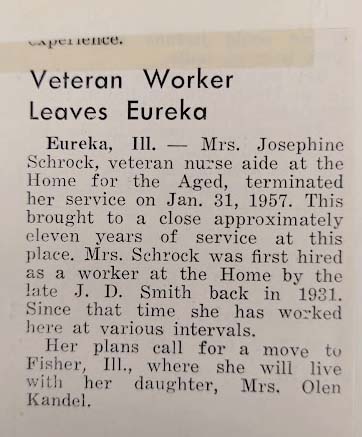

In the midst of caring for her family, minding the farm and working outside the home, Grandma was deeply involved in a broader mission. A newspaper article in 1966 reported:

While celebrating Josephine’s eightieth birthday the Women’s Missionary and Service Auxiliary of East Bend Mennonite Church honored her almost 50 years of service to the organization. She helped organize the original Sewing Circle in 1917, working with other women sewing for Christian mission, fellowshipping together, and discussing any “opportunities of visiting the sick and unfortunate locally and helped them in their times of need. She served as treasurer of the State Sewing Circle for five years and State president in 1926. When the office of Secretary of Literature was created, she served there. Then she was responsible to all the member circles for their missionary literature…She has given unselfishly in her lifetime, many hours, days, weeks helping others. One grandmother recalled that Mrs. Schrock administered ether to her at the birth of her first child. This was an uncommon procedure in those days…Never idle, she spent a number of years helping at the Home for the Aged in Eureka, Illinois, and working at Goshen College, Goshen, Indiana.

When Elmer and Orval were old enough to be on their own and Eunice had finished her eight grades at Brown Township School, Grandma decided it was time for a little wanderlust of her own. She sold her twenty acres in Fisher and moved back to Eureka where the Yordy family was well established. Her brother Ezra, a minister at the Roanoke Mennonite Church, farmed with his wife Carrie (Good) just south of town: their son Maurice lives on the farm yet today. Another brother, Walter and his wife Alma (Eigsti), occupied a large farm a few miles south of Secor, on Meridian Road. Grandma’s other siblings and her mother lived in the area as well.

The Joseph and Elizabeth Roeschley Yordy Family about 1928

Front row L to R: Alta Yordy Graber, Florence Yordy Schrock, Ethel Yordy Troyer, Eunice Schrock Kandel, Richard Yordy, Dorothy Yordy, Edith Yordy.

Middle row L to R: Alma Eigsti Yordy, baby Ruth Yordy Kellar, held by Carrie Good Yordy, Josephine Yordy Schrock, Elizabeth Roeschley Yordy, Anna Yordy, Ella Yordy.

Back row L to R: Walter Yordy, Ezra Yordy, Jonas Yordy, Lewis Yordy, Elmer Schrock, Orval Schrock, Alvin Yordy.

Note: Aaron Yordy is missing, and Maurice Yordy was born several years later.

The Mennonites had established a home for elderly congregants at the north end of Eureka in 1922—an old people’s home, as it was first called; later names were Home for the Aged, then Maple Lawn Homes, and finally Maple Lawn Health Center. But in this article it will be called by its shorter name, Maple Lawn.

(L to R) Josephine Schrock, Rose Eigsti Graber, Mattie Schertz, name unknown, Esther Wolber, Edna Zehr

Mom thrived during her years at Eureka High School, meeting new friends, living close to the Yordy cousins, while staying in close touch with her Heiser cousins in Fisher.

Yes, Mom thrived, but it was very different being the child of a single parent and living in an “old people’s home.” Archie Unzicker (1917-2008) tells of a date he had with my mom, saying, “[it was the] only time I ever picked up a date at the old people’s home.” Mom told of times she’d walk back and forth to school during the Christmas season peering into homes along the way. She would see families gathered around tables enjoying each other’s company, and she thought to herself, “Someday, that will be me.”

Grandma’s later life

Where did she go from there? To Fisher to become resident housekeeper for her daughter Eunice. True to her goal, Eunice had married Olen Kandel and by that time they had four children. Mom, trained as a teacher at Goshen College, had met Dad while teaching high school in Berlin, Ohio. After marriage they settled near Fisher, Illinois, where Dad became tenant farmer for Alva Cender, who had married Edna, one of Mom’s Heiser first cousins. Mom was soon to resume her teaching career, thus, Grandma Josephine moved in to keep the home fires burning.

As for me, a child growing up in that household, it always seemed natural to have Grandma Josephine there—she was an essential part of the operation. We frequently made Sunday afternoon trips to Eureka to visit our Yordy relatives, including Grandma’s brother Aaron who had become an invalid residing at Maple Lawn. I remember visiting Aaron as a boy with my Dad on the second-floor men’s ward.

Perhaps because Grandma lived with us for so many years, I always felt comfortable around older people, so when as a young man I was offered the job as Administrator of Gibson Manor Nursing Home in Gibson City, Illinois, I jumped at the chance. But it was only a year later, when I was offered a similar position at the Mennonite home in Eureka, that I again, not surprisingly, jumped at the chance. After all, my family had a history there—right?

Earl Greaser, who had been Administrator at the home for twenty years was having health issues and his doctor suggested he find a less stressful job. The year was 1976 and as a twenty-eight year old I threw myself into the work at Maple Lawn with all the gusto I could muster. I was told I had big shoes to fill and I intended to prove I could do it.

Five years earlier, the steps to Grandma Josephine’s second floor bedroom in my parent’s house in Fisher were becoming too much for her. With Mom teaching all day and the house now empty of children, Grandma once again decided to leave Fisher and move back to Maple Lawn—this time as a resident.

But in 1977, only a year after I had become administrator at Maple Lawn, Grandma Josephine had a stroke and was moved from Shelter Care to the nursing home. I think by then she was ready to call it quits, as she had said in a 1971 taped interview with a granddaughter, “I’ve lived my life!” Grandma didn’t willingly give herself to rehab in the nursing home and died three weeks later. My biggest regret is that while I was in the same building I was not with her when she died. Sue Madden, R.N. on duty, came into my office several times to tell me Grandma was near the end, but I thought what I was doing was very important. The third time she interrupted me, she said, “Your Grandma is dead.”

When her estate was settled, a tenth ($329.37) was given to the Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities at her request, indicating her funds were almost depleted when she died.

On a cold winter day in January of 1977, with snow at least a foot deep, we buried Grandma Josephine next to Grandpa Albert, who had been waiting for sixty years. During those sixty years, Grandma Josephine was always there for us—a person of resilience and servanthood.

Josephine Yordy Schrock: No judging, no gossip

Written in 1978 by Mary Alene Cender Miller, while living in Hokkaido, Japan, and printed here with her permission.

Great-aunt Josephine with her unique handicap caught my attention when I was seven. In her late fifties she had slipped on the ice and received a head injury that left her without a sense of smell or taste. “It’s no problem to cook for myself now,” she would quip.

This cheerful acceptance of her lot impressed me as a child long before I was able to evaluate her other qualities. I did not ponder then that she had been widowed young and had raised her three children alone. I did not notice that she had always worked hard and had complained little.

By the time I had children of my own, we were living in Japan in a culture in which old age is supposedly revered. While many people over sixty are taken in and cared for, even indulged by their children in the Confucian tradition of filial piety. I sensed there were many problems in these family arrangements. People had not necessarily acquired true inner peace in their later years after all.

Apparently then, adequate physical provision in retirement is not the whole answer; the human spirit desires something more. For me, Aunt Josephine with her sedate Christian poise had this “something more.” She was one person I had to see on furlough.

In 1968 she taught me two things. I pressed her for historical information. She had personally known both of the great-grandmother Marys after whom I am named. I wanted to hear about my ancestors and about the local congregational lore that I knew her sharp mind kept stored up. She gave me the facts all right, but she would not be drawn into comment or interpretation that cast unfavorable light on anyone.

I came away (wickedly) missing hearing the stories I knew she could have told. But at the same time I admired a person who could control her tongue at eighty-two. Aunt Josephine made me want to acquire judicious, gracious speech. And, like she had, I knew I’d have to start practicing it immediately, in my (comparative) youth.

The other thing I learned from Aunt Josephine that summer also reflects on her inner life. She had a quick and accurate mind, but she was not judgmental. I found her not at all confused by her great-nieces and nephews, by her grandchildren and children, none of us perfect and many of us having made decisions in life that clashed with her piety and faith. I was impressed with Aunt Josephine’s tolerance and broad world view. She had turned over judging to the Lord.

The last furlough I saw Aunt Josephine she was eighty-eight and living in a retirement home she had chosen among relatives and friends. Though she was unmistakably reduced—to a roommate, a bed, a dresser, and a rocking chair—and frail in appearance, she was dignified and content in spirit. Her very posture seemed to challenge: someday you may live apart, not only from closest family, but you may have to give up things. (My books! My papers! My files and plants and antiques!. . .) Better to hold them lightly now.

Aunt Josephine died last year at ninety, impatient that she couldn’t have gone sooner because, above all, she didn’t want to cause anyone any trouble in old age. And then she found herself in the hospital, things out of control. Before she lapsed into her final coma, I am told, she cried sometimes because she couldn’t die faster.

At first I could not permit Josephine Yordy Schrock, my model of spiritual strength, these tears, this little weakness. But then I saw that even at the last she was saying something about how to die. If it is possible she was harboring a tiny pocket of pride all along, by it she has sobered me up about areas of pride in my own life I can get to work on right now.

Was Grandma Josephine a Non-conformist?

A day or so after finishing collaboration with my first cousin, Frank Kandel, on his article for IMHGS, I sat at the breakfast table reading an article by LaLeita N. Small on the website of Christians for Biblical Equality (cbeinternational.org). She attended a School of Divinity and was participating in a seminarian retreat, when the leader of her discussion group referred to her and one other older (40s) woman as her nonconformists.

In the 1970s my husband and I were part of the small group in the Chicago area that eventually became the international organization, Christians for Biblical Equality. In those days I suppose Del and I were seen by some as nonconformists as well. Now, I began to realize that my Grandma Josephine’s life could also be called one of nonconformity.

In the 1930s, women generally sought a new husband when the previous one died. They needed someone to insure their well-being and future. But Grandma’s parents had opened her eyes to travel and working for others, so after husband Albert’s death she went to work on her farm, and in others’ homes to make ends meet—in the Depression! She was decisive, but not demanding, exploratory, and willing to change with the times when many of her contemporaries were slow to accept new ways. She helped others rather than seeking help for herself. She was a student and teacher of the Bible; albeit at the time, within certain structures of her church.

During her later life she accompanied my parents, along with my maternal grandmother, on a fishing trip to Canada. I realize now this no doubt reflected her love of travel. I sent her several postcards from countries I visited while working with an international organization, in the hopes she would enjoy the “virtual” visit.

At the end of her article LaLeita N. Small wrote:

How do I feel about being labeled as a “nonconformist”? After rehearsing the teachings of Christ and Paul’s authoritative advice, I would say thank you to my group leader. Thank you for prophetically affirming me and identifying that I am an agent of change. I am a voice in the wilderness crying out to prepare the way for my brothers and sisters. I am charged to encourage others, not to conform to society’s status quo but to transform to a renewed mind in Christ.

Would Grandma agree with LaLeita? Perhaps she would—in her own quiet, non-demanding, accepting way.

Written by Donna Schrock Birkey

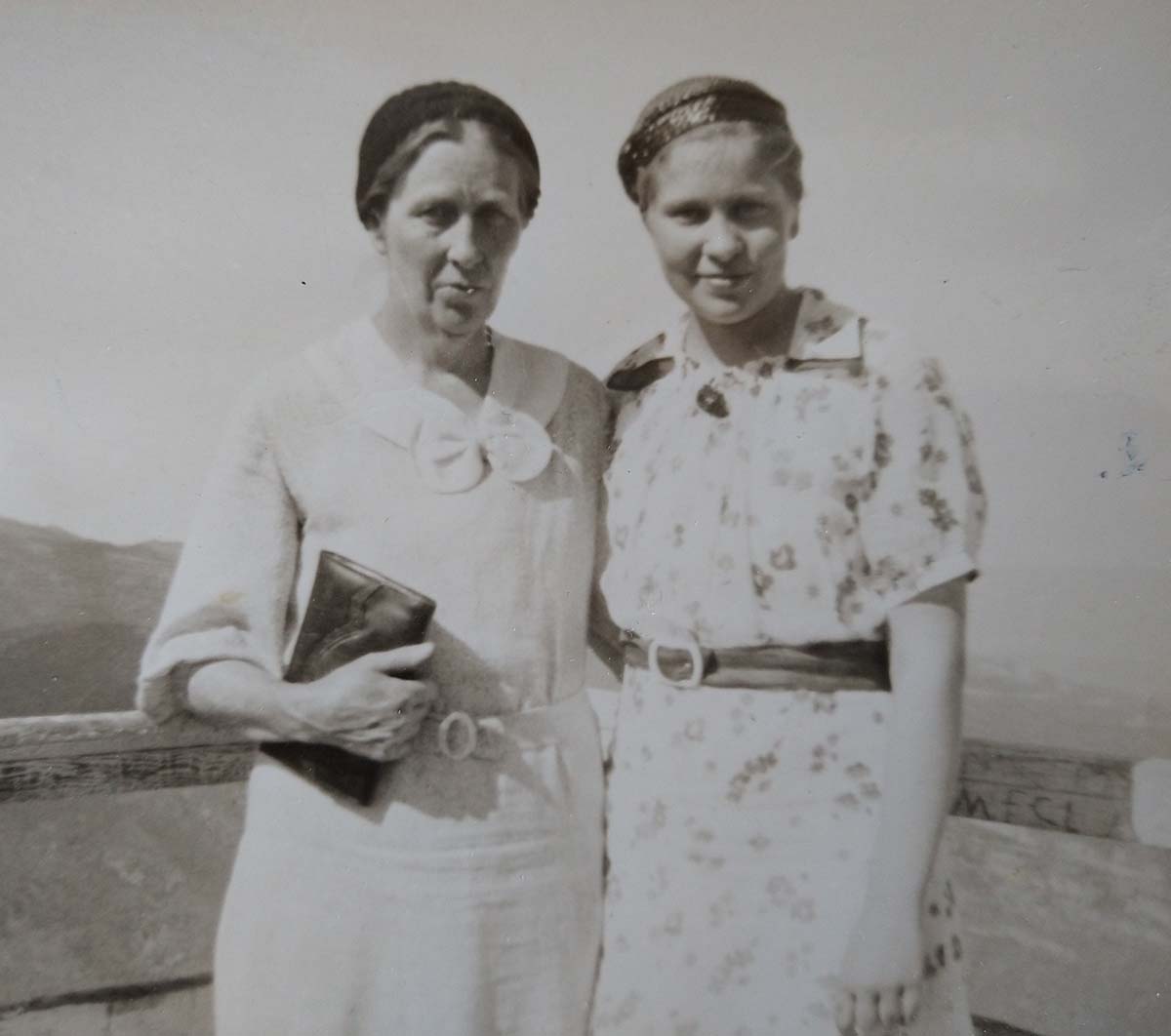

Left to Right: Effie Blackwell Park, Laura Mae Park Schrock, Josephine Yordy Schrock